It is an unexpected paradox that one of the hardest endurance motorsport disciplines to date required no competition licence. In fact, owners of competition licences were not eligible to compete and it was in the very strictest terms an amateur competition. The Camel Trophy though, which celebrated its 40th Anniversary in 2020, was no stranger to paradox. It was a fevered (sometimes literally) race across the world’s most inhospitable wildernesses that rewarded those that stayed behind to help, an international event that pitted countries against one another but did more to break down borders than a lot of other sports. It was a cigarettte-sponsored, 4×4 marketing extravaganza that helped scientists access to study remote parts of the world and raise awareness of threatened landscapes and cultures. However, despite the paradoxes contained within, the Camel Trophy was singular in its purpose: the pursuit of adventure.

“Neither a race nor a rally, Camel Trophy was first and foremost an adventurous expedition. It did include an element of competition where participating teams could test their 4×4 driving and mechanical skills, endurance, courage, stamina, perseverance and resilience against the worst that nature could offer.”

IAIN CHAPMAN

In 1980 the innaugural event consisted of only three two-man teams from Germany. Using hired Ford Jeep CJ6s; they embarked on a 12-day, 1600km odyssey along the Transamazonica Highway, also known as the ‘Highway of Tears’ from Belem to Santarem. Only two of the Jeeps made it to the finish, the third was left burning in a petrol fire in the forest, the remaining (winchless) Jeeps crawled to the finish with their battered, bitten and exhausted passengers. The first Camel Trophy was small in comparison to subsequent events but it was no less ambitious and littered as it was throughout with isolation, dust, mud, rafts, gold, insects, disease, fire, breakdowns, bandits, and bribery – it set the bar for adventure at 11.

The Camel Trophy was an instant success. Land Rover started providing vehicles in 1981 and continued to do so until 1998 (there was an event in 2000, but that was in boats!), the two brands become synonymous with one another and the annual event went truly global. Each year more countries fielded teams and each year the numbers of hopeful amateurs boomed, by the mid-80s; hundreds of thousands, by 1989; millions. Each country devised its own selection process to whittle thousands of entrants down to just two fortunates. Strangely enough, despite Land Rover’s involvement, Britain didn’t field a team until 1986. Royal Navy and retired SAS specialists were engaged to create gruelling trials in muddy corners of the British Isles to test the resourcefulness, stamina, skills and mental resilience of would-be competitors.

“The main emphasis of Camel Trophy was more toward testing human endurance and adaptability than pure competition. All participants were amateur and anyone, over the age of 21 from a participating nation could apply to take part – provided they did not hold a competition driving license or were full-time serving members of the military. The essentials were fitness, common sense and an adventurous spirit.”

IAIN CHAPMAN

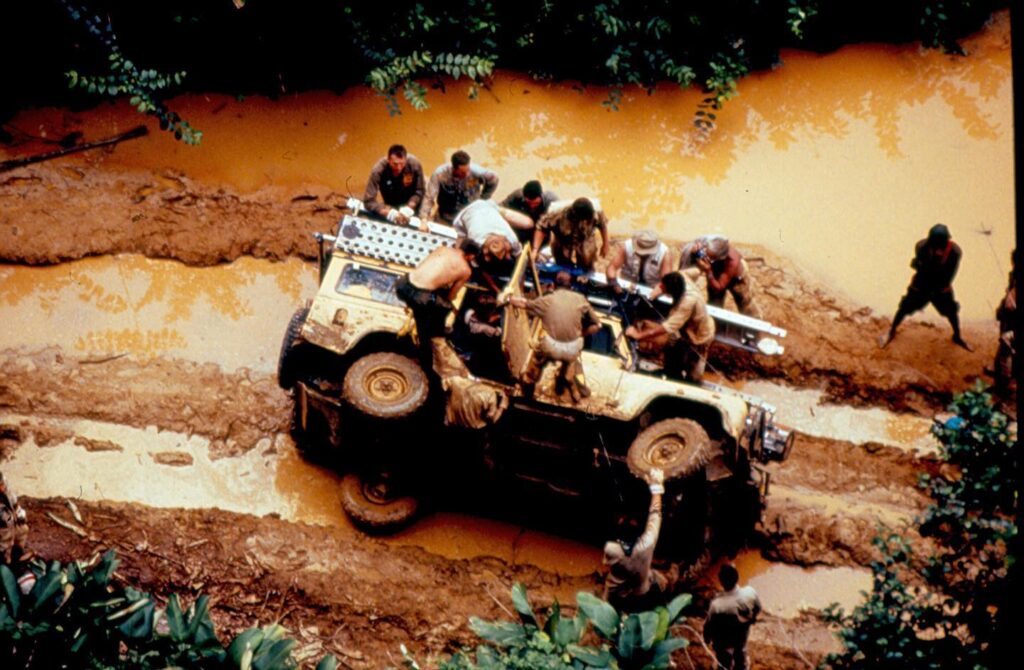

Bob Ives was one of the hopeful British applicants seeking adventure. Bob tried for selection on three occassions, on two occasions reaching the final weekend of tests. A twist of fate and an unfortunate coming together of a Mini Moke and a Spanish bus on the final selection weekend landed Bob and his brother Joe the prized gig. What happened next is generally considered to be the high water mark of the Camel Trophy. The two brothers went on to win the hardest, longest, muddiest, hottest, and most exhausting event of them all: Amazon 1989. The slick red Amazonian mud made the two weeks of convoy a desperate ordeal, so delayed were many of the teams that the special tasks planned for the end of the event had to be cancelled altogether. A contemporary press release records a distance travelled of 4km… in 18 hours. Bob and Joe were contenders for the Spirit of Camel Trophy award as well as being contenders for outright victory. A puncture for the Spanish team in the closing miles of the event secured the brothers’ vicotry. The Belgian team were on hand to recovery the Spanish Defender and clinch the team award.

“There were stretches where we put two anchored cars pulling another one and nothing happened. We had to dig for half an hour, 40 minutes to try to get the car out of that hole and thirty metres later fall into another one.”

RICARDO SIMONSEN, TEAM BRASIL 1989

If anyone is in any doubt as to the veracity of their achievement in the Amazon jungle, in 1989 the Ives brothers were awarded the coveted Segrave Trophy which recognises “Outstanding Skill, Courage and Initiative on Land, Water and in the Air’. Other Segrave Tophy winners may be more familiar to Goodwood fans, names like; Malcolm Campbell, Stirling Moss, Bruce McLaren, Jackie Stewart, Barry Sheene, Colin McRae, Andy Green, Adrian Newey – it really is a hallowed list. Bob speaks with humour and humility about his experiences with the Trophy. He returned to drive support vehicles and lead the planning of routes and special stages for subsequent Trophy events and has been involved with expeditions ever since as well as managing the family farm, but he is unequivocal about his reason for wanting to be a part of the Camel Trophy; adventure.

“Sleep when you get home”

BOB IVES, TEAM BRITAIN 1989

It may be a surprise to some that the composed and always reliable rally and F1 pundit Tony Jardine was once a parasite-infested, bandit-dodging, Camel Trophy winch-man. Having been involved with Camel on the F1 circuit Tony found himself managing public relations for Camel Trophy in 1987, brought in following the collapse of the special tasks in Madagascar. Tony and his team restructured and professionalised the organisation of the tasks and their marshalling to ensure a level playing field for all of the competitors. Tony then steered public relations through the event’s most successful period and experienced no less than 10 Camel Trophy expeditions in the flesh (literally in some cases). Tony is in no doubt that 1989 was the event that best captured the spirit of the event, 1989 was the most adventurous Camel adventure.

Tony recalls with a certain twisted fondness encounters with crocodiles and aligators, being stalked by a pride of lions, communication blackouts on the African plains, delivering a Defender differential by rail handcar, negotiations with bandits at the head of the Iguazu Falls, armed tomb-raiders, Paraguayan cowboys firing pistols at the convoy and death-defying plane rides over the sprawling Amazon jungle. Tony even remebers with surprising equanimity, sweating and hallucinating whilst interviewing Nigel Mansell at the Canadian Grand Prix as parasites tracked pathways under his skin and fly larvae crept from eggs in his ankles following the 1989 jungle odessey. He also remembers the survey stations that were built, the pioneering Siberian event in 1990, the local communities and rich divergent cultures that were encountered, the medicines that were delivered, and the overwhelming and unifying sense of achievement at the end of each Trophy. It is difficult to resist the sense that if they could do it all again – Tony and Bob would, quicker than they could say “Sand Glow Discovery”.

“It’s difficult to understand and impossible to explain. At the time of Camel Trophy 1990, the great Soviet Empire was on the verge of its death. A lucky star led us into the wonderful world of Camel Trophy and gave us dozens of friends from countries that since childhood were considered our enemies. We welcomed them, showed them a few wild and harsh corners of Russian nature in Siberia. 1990 marked the return of the American team to Camel Trophy and it was another good symbol! Now we are members together of the of Camel Trophy family!”

MARK PODOLSKIY, TEAM SOVIET UNION 1990

It would be disingenuous to suggest Tony wasn’t rewarded for his time with the Camel Trophy, that relationship contributed significantly to the success of HPS Jardine but as he boyishly recalls his time with the Trophy it becomes abundantly clear that the real reward was the experience itself.

The Camel Trophy is something of a paradox. At once a huge, global PR exercise for Land Rover and Camel cigarettes and at the same time an extraordinary amatuer endeavour. Bob Ives, although a fan of the new Defender, ruefully reflects that modern 4x4s, with their reliance on electronics, couldn’t manage the arduous Trophy routes. Even if they could the routes themselves are much less wild then they were even in the 1990s. In 2021 in a world obsessed by reward and validation the convoy of vehicles might not be delayed so much by sucking mud and looting bandits as it would be by Instagram photo shoots and Tik-Tok vlogs. Adventure these days is packaged, filtered and made accessible to all, but to experience raw exploration today a person needs to be at the peak of their sport and probably a professional. The Camel Tophy occupied a singular moment in time when the desire, technology, resources and environment converged to make unedited adventure accessible to the amateur. Paradoxically forged in a decade where winning was everything and everyone was out for themselves the Camel Trophy gave meaning to the idea that what really mattered was taking part, that working together for a shared outcome was a victory worth winning.

0 comments on “Winning Isn’t Everything”